Background

Tom Byrne's 2009 article:

Pirates or liberators? The British invasion of Buenos Aires in 1806

British invasions of the Río de la Plata

THE 1st/71 Highlanders and the Bethlemites in Buenos Ayres ~ This article depicts some of the most fierce combats during the 1806/7 British invasions, the medical assistance provided by the Bethlemites and the possible burial places of the British troops. Courtesy Dr Eduardo C. Gerding

Also see Norberto Perez' list of Argentinian placenames

April 12th 1806 - Received orders to embark on a secret expedition - a sergeant’s party under the Command of Sergeant Henry of the 20th Dragoons, two six-pounders, a few Artillery men commanded by Captain Ogilvie, and the 71st Regiment, under Lieutenant-Colonel Pack, the whole commanded by Brigadier-General Beresford.

Lieutenant-Colonel Pack ( c. 1772-1823)

(William Carr Beresford, Viscount Beresford 1768 - 1856)

April 14th 1806 - Sailed from Table Bay; headquarters on board the ‘Ocean’ transport, on board of which ship I was.

Table Bay

April 20th 1806 - A dreadful storm arose which lasted during the night. Our mizen mast went overboard. When daylight appeared no ship of the fleet was to be seen but our own dis-masted one.

April 21st and 22nd 1806 - All hands employed in getting up a jury mast. The instructions of the master could not be opened until we arrived in a certain latitude; we therefore sailed the same course we were in before the storm.

April 29th 1806 - A sail was discerned far astern in our course; appeared to be a frigate, gaining on us every moment; at 6 p.m. so near that she fired a shot to bring us to; great consternation on board, we not having a serviceable gun in our ship, and the enemy having a fleet in these seas. At nightfall she came alongside, and hailed us as to our name and destination, and ordered a boat and officers to be sent on hoard. The men (200) were kept between decks, and our ship appeared like a merchant vessel. The captain gave her a Dutch name and answered that all our boats were washed overboard in the late storm. The strange ship then lowered a boat and sent an officer in uniform and a crew alongside. The officer came on board and went down to the cabin and overhauled the captain’s papers. During this time we were in the greatest suspense; but to our joy she turned out to, be an East India pacquet, bound for England, by whom we sent home some letters. This night opened the instructions, which were ‘to sail for the River Plate, and, in case of not finding the fleet there, to return to the Cape.’

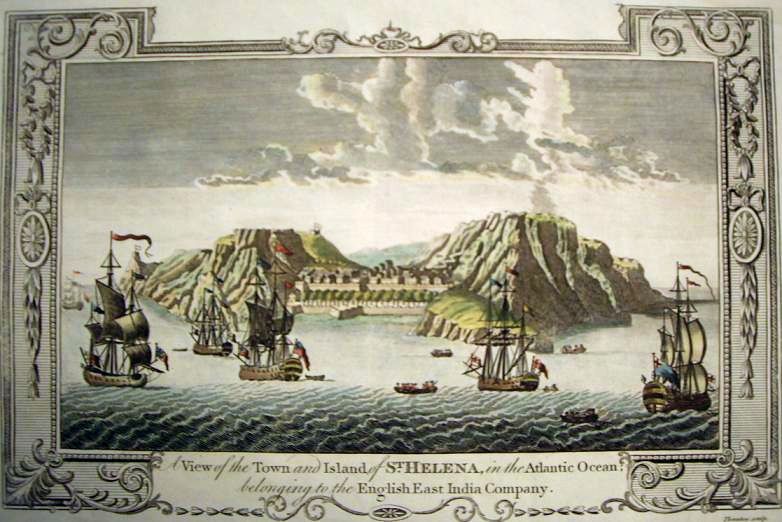

April 30th 1806 - The remainder of the fleet under Sir Home Popham, with the ‘Diomede’ 74, the ‘Diadem’ 74, the ‘Narcissus’ frigate, the ‘Leda’ frigate, and the ‘Encounter’ gun brig, arrived at St. Helena, and received a reinforcement of two hundred men of the St. Helena Corps, to replace the 200 on board the ‘Ocean,’ supposed to have been lost in the late storm.

Sir Home Popham (12 October 1762 - 2 September 1820)

From: Battle of Blaauwberg 200th Anniversary Site

May 2nd 1806 - Sailed from St. Helena. (5)

St Helena

also see: Views of St. Helena 1815

May 8th 1806 - Made the River Plate, where the ‘Ocean’ joined. During the voyage provisions and water became scarce, so that for the last eight days we had nothing but wheat boiled in salt water, and a very small allowance of that. The men could not be persuaded but that there was plenty of provisions in the hold, when the Commanding Officer, Major Tolley, ordered a deputation from them to be sent down under my command, and found only three days’ provisions, which was reserved for the landing, and quite satisfied the poor fellows.

May 15th 1806 - The troops removed from the men-of-war into the transports; the ‘Diomede’ and ‘Diadem,’ being too large to proceed up the river, remained in front of Monte Video. The small vessels sailed up this evening.

The army now advanced, and drove the enemy from their position on the river. (8) We set to and lashed three or four of the small craft together, and procured planks to make a gangway. All passed over and advanced towards Buenos Ayres. On our way we were met by the Alcalde and the Chief Civil officers of the city, who came out in their official robes with an offer to deliver up the city to the English. We marched into town and took possession of the castle and the barracks called Rangaris. [?]

In order to make our forces appear more formidable, we were ordered to take double distance in column on entering the town, but the Spaniards soon discovered our strength by the rations daily drawn. I was accosted one day by an inhabitant who enquired as to our numbers, which I exaggerated some hundreds, when he very pertinently asked ‘how were they fed, as rations were only issued for such a number.’ I accounted for it as men in hospital, servants, etc., but it would not do, they knew to a man our strength.

To our surprise we found a number of English men and women; they were part of the crew and convicts of the transport ship ‘Sarah,’ who rose on the captain and those who were faithful to him on their passage to Botany Bay. They murdered the captain and mate, and carried the ship into Buenos Ayres, where they sold her. Some of the female convicts were well married, and the male working at their different trades. One we found very useful, named Patrick Carey, and another, Smith, that General Beresford brought to England. The former man got into the Commissariat, and served with us at the Corunna retreat. He was drowned in the bay the morning we cut our cables on leaving it. The fellow that killed the captain by a blow of a hatchet as he came up the companion steps, and two females, were the only persons of the whole that followed the dissolute lives they were accustomed to lead in England.

After being some time in peaceable possession of the town, a man cleaning his firelock in one of the barrack rooms happened to stick his ramrod in the ground floor, which instantly disappeared. When searching for it we found that the whole range of the barracks was undermined from the other side of the street where there was a Convent of Friars.

On examination we found that they had been at work many days and had mined under the main street and had actually placed some barrels of gunpowder and would, if not so fortunately discovered, have blown us to atoms.

The day we entered the town the Viceroy, (9) with a detachment of Dragoons, left it, taking with him sixteen wagons loaded with doubloons and dollars, and took the road to Luchan. Captain Charles Graham, of the 71st, with his company and a few dragoons was dispatched after him, and succeeded in taking the whole, which he brought into town, and it was put on board the ‘Narcissus’ frigate and sent to England with the dispatches by the Honourable Captain Dean (afterwards Lord Muskerry), of the 38th Regiment, Aide-de-Camp to Brigadier-General Beresford.

About this period the General received information that there was a likelihood of a rising of the people, under Pueridon, one of the municipality. Arms were secreted in the town, and nightly assemblies took place. Colonel Linears (10) a French officer on parole, collected great numbers at Colonia on the other side of the river.

Santiago de Liniers, 1st Count of Buenos Aires (1753 - 1810)

A few days previous to this the Dutch recruits (11) we received at the Cape deserted to the enemy, and one of them was actually taken with the lighted match in his hands at one of their guns. He was sentenced to be shot by decree of a court martial. The Bishop of Buenos Ayres waited on General Beresford and offered two thousand dollars to save his life, but was refused, and he was accordingly shot next day.

August 9th and 10th 1806 - The enemy advanced and took a small post in the suburbs, where the 71st had a sergeant’s guard, and massacred Sergeant Kennedy (who was in charge) and the whole of the men he commanded. They then advanced by all the streets leading to the great square (where our small force was drawn up). Our position was commanded by the enemy, who occupied the tops of the houses and the great church, (12) it being completely secured by the parapets that surrounded the flat roofs. We were picked off at pleasure. At a gun near the church, three reliefs, in a short time, were killed or wounded. Lieutenant Mitchell and Ensign Lucas, 71st, were killed here, with Captain Kennet, Royal Engineers. The General, seeing further resistance was vain, went into the castle and hoisted a flag of truce: our small force was ordered in and the gates closed. After a conference between the General and an Aide-de-Camp of Linears, we surrendered to the greatest set of ragamuffins ever collected together.

Our loss was:-

Royal Engineers.-1 captain killed.

Royal Artillery. - 1 captain and 1 lieutenant wounded; 3 rank and file killed and wounded.

St. Helena Artillery. - 1 sergeant wounded; 9 rank and file killed, 13 wounded; drivers - 1 wounded.

71st. - 1 lieutenant and 1 ensign killed; 1 lieutenant-colonel and 1 ensign wounded; 1 sergeant killed and 5 wounded. (missing); 1 drummer killed; 24 rank and file killed and 67 wounded.

Royal Marines. - 1 captain and 1 sergeant wounded; 6 rank and file killed, 5 rank and file wounded, 8 rank and file missing.

St. Helena Regt. - 1 lieutenant wounded; 1 sergeant killed; 1 rank and file killed, 4 rank and file wounded, 1 rank and file missing.

General total, 144.

Died in Hospital. - 71st, 5; St. Helena Regiment 1; Marines, 1; Artillery, 3; total, 10.

NAMES OF OFFICERS KILLED

Captain Kennet, Royal Engineers.

Lieutenant Mitchell and Ensign Lucas, 71st Regiment

Wounded.

Captain Ogilvie and Captain M’Kenzie, Royal Artillery.

Lieutenant Sampson, St. Helena Regiment.

Lieutenant-Colonel Pack and Ensign Murray, 71st Regiment.

Lieutenant Cowsel, Royal Marines.

August 12th 1806 - We were marched out of the castle between files of Spaniards and Creoles (the enemy having only one small regiment of regulars), and crowded into the Cabildo, or town house, amid the shouts of an infuriated rabble. The clergy and women vied with each other in kind acts to the prisoners. The writer and Colonel Pack were in the street surrounded by the mob, who were dragging the Colours of the 71st through the gutter, crying out for the head of an Englishman, when a worthy Spanish gentleman came up and rescued us from our perilous situation, took us to his house, and treated us most hospitably. We remained till next morning. The Spaniards acknowledged to have lost seven hundred men from the 10th to 12th August.

August 18th 1806 - I ventured out, protected by a worthy priest, and was met by a contractor who supplied us with bread during the time we occupied the town. He, with the most unfeigned joy, clasped me in his arms and informed me he had searched among the dead, the hospitals, and prisons in vain for me and gave me up for lost. This good man’s kindness continued during our stay in Buenos Ayres. He visited me daily, and the night previous to our being sent up the country brought me as much excellent biscuit as a huge black could carry, saying, ‘You have to travel some hundreds of miles, where nothing but beef without salt can be procured,’ which proved to be the case. It proved of great service to me and my friends on the journey. Another instance of the Spanish friendship I can detail. After we were made prisoners the Spaniards formed a Corps of volunteer light horse, and copied the uniform of our 20th Light Dragoons. They were composed of gentlemen. One of them, Don Pedro Gasper, took a great fancy to me and offered to send me to a friend’s house some miles in the country, but I preferred sharing the fate of my countrymen. Having no money for the march I offered him my watch for sale, but understanding me imperfectly he brought me a man who could speak a little English, who made my intentions known to him, when the good man thrust his hand in his pocket and threw out thirty or forty doubloons, and said, ‘When that is out you shall have as much more.’ I declined the generous offer with heartfelt thanks.

COPY OF THE ARTICLES OF CAPITULATION

The British General having no further object for remaining in Buenos Ayres, and to avoid the unnecessary effusion of blood, and also the destruction of property of the inhabitants of this city, consents to deliver up the fort of Buenos Ayres to the Commander of His Most Catholic Majesty’s forces on the following conditions:-

First. - The British troops to march out with all the honours of war, to be considered prisoners of war, but to be embarked as soon as possible on board the British transports now in the river, to be conveyed to England or the station they came from.

Second. - The British on their entrance into this place made many prisoners of war, which remained on their parole, and, as the number of officers is much greater on one side and of men on the other, it is agreed that the whole shall be exchanged for the whole. The English transports returning to their places of destination as Cartel, are to be guaranteed as such by the Spanish Government from capture on the voyage.

Third. Provisions, etc., will be furnished for the passage of the English troops according to the usual custom in like cases.

Fourth. - Such wounded of the British troops as cannot be removed on board of ships shall remain in the hospitals at Buenos Ayres, either under charge of Spanish or British surgeons, at the option of the British General, and shall be furnished with everything necessary, and on their recovery sent to Great Britain.

Fifth. - The property of all British subjects in Buenos Ayres to be respected.

(Signed) Wm. CARR BERESFORD,

Santiago Conisidido Linears. (13)

Notwithstanding this capitulation, on the Spaniards hearing of a reinforcement arriving in the river from England, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Backhouse, (14) orders were issued to send the prisoners into the interior of the country. The men marched off to Tuckaman (15) Cordova, Mendoza, etc., and the General, Colonel Pack, Captain Arbuthnot (Aide de Camp), Captain Ogilvie (Royal Artillery), and Assistant-Surgeon Evans (71st Regiment) remained in Luxan, twelve leagues from Buenos Ayres - the officers to St. Antonia, Chappeles, Ronches, etc. The writer of this to St. Antonia. We passed through a beautiful plain covered with innumerable herds of wild horses and cattle.

Here we received the news of the murder of Captain Ogilvie on the 27th of November by a creole, when he and Colonel Pack were riding out. The Colonel had a most narrow escape, the murderer having thrown a lasso at him in which he got, entangled and would have shared the fate of his friend but for the opportune appearance of two men.

We were well supplied by our landlord Don Pedro Gomez with good bread, beef and mutton, paying him well for the same - viz., about 4/6 per bullock, and 2/- per sheep. We sometimes got a little country wine from itinerant dealers from Cordova, who travelled vast distances before they could meet a customer. We had a captain’s guard of Spanish dragoons. We also received three months’ pay from the Spanish Government - a dollar per day. Through the whole of the country we traversed we scarcely met an inhabitant, except at distances, where large towns were traced out with streets of squares, with a wretched mud fort or perhaps a dismounted gun, and an unfortunate corporal with two men sent to keep the natives in awe. From this place Major Tolley and Captain Adamson made their escape to the River Paraguay, which falls into the Plate, and after innumerable hardships obtained a boat, hiding during the day and rowing all night, levying contributions of provisions on any house where no male person was to defend it, and arrived in safety at Monte Video. Captain Jones, encouraged by this success, formed a plan to follow their footsteps, but while waiting for an issue of pay, unguardedly made his intentions so public that the Spanish captain knew to the hour when he was to set out, with his servants in disguise as Creoles, and the route he was to proceed, and allowed him to proceed about six leagues, and in a wood secured them both and carried them prisoners to Cordova - there kept closely confined during our captivity.

About one league from St. Ignatia was another Quinta, where Captain Duncan M’Kenzie (then Paymaster M’Kenzie) and a few officers lived. Captain M’Kenzie’s servant was a married man, and his wife a beautiful Irish girl. She was sent by her master rather late of an afternoon to St. Ignatia for change of a doubloon, which, on her receiving, was observed by two Creoles, who followed her, and midway between the two Quintas barbarously murdered her; but on discovering next day that she was a Catholic, their grief and remorse was beyond measure. Here I first saw the process of interment in Catholic countries. The grave is dug about ten feet deep, the body without a coffin laid in it, and quick lime thrown over it, then a layer of earth, which is beaten down with something like a pavior’s mallet, until it is formed into a hard patie, and so on, layer succeeding layer, until the grave is filled up, which occupies the work of some days.

We lived here very comfortably until the month of August, when we were informed that we should soon be on our way to England; that the British Government had sent out a force of 10,000 men under a General Whitelock, who was obliged to surrender with his whole army to the Spaniards, and that one of the articles of capitulation was our release. We laughed at the idea, (16) as we took Buenos Ayres with about 1000 men, and could have marched over all Spanish America with 10,000. We provided ourselves with ponchos, a kind of blanket with a slit in the centre; by putting your head through it forms not an ungraceful kind of cloak. It is worn by all the natives; the better sort is made of cotton and makes a good quilt. It serves as a blanket at night; and out of a coarse cloth made of hair and wool we contrived to make a sort of tent that kept the dew of the night from us.

On arrival at Buenos Ayres we were marched along the river side and embarked in boats for Monte Video. We could observe that the fortifications of the town were much improved from the time we took it. On our arrival at Monte Video we were inspected by General Whitelock; and a motley crew we were, without arms, and mostly dressed in Nankeen jackets and trousers. One of the articles of capitulation was that Monte Video should be evacuated by every British subject on a certain day, and the confusion on that day was beyond description - hundreds of merchants who came with all sorts of merchandise from England lying on the beach with their goods and could not obtain a passage. The troops were, of course, provided for in the men-o’-war and transports. The writer of this was sent, on the day of evacuation, by Colonel Tolley, on shore to purchase articles for the Regiment, and brought a man with two thousand dollars on his back for the purpose; but the Spaniards, conceiving that it was plunder, detained us, and would probably have murdered us but for the interference of one of General Whitelock’s staff, who explained to them our mission.

About eight days after leaving Monte Video, a most violent storm arose, which increased about midnight, when we discovered that the ‘Princesa’ had sprung a leak. All hands were called on deck and the chain pumps manned, and lanterns hung in all parts of the rigging, and guns fired as signals of distress; but the night was so dark and the hurricane so violent that no assistance could be given to us. The cries of the women and sick, the rattling of the wind among the shrouds, was truly frightful, as we expected every moment to go to the bottom. When daylight appeared the wind abated, but the sea ran mountains high, and the Admiral, perceiving our colours half-mast high, bore down upon us and hailed. us. On hearing our condition he sent two carpenters aboard to inspect the ship, who pronounced that she could not swim for two hours more. By this time the water was up to the second (or Orlop) deck. On their return (the carpenters) to the ‘Lion,’ the Admiral’s ship, a signal was made for the Fleet to lie to and lower all their boats, and rendezvous round the ‘Princesa.’ Providentially at this time the wind had quite abated, and the sea comparatively calm, and everything got ready to embark in the boats. The confusion, as may be expected, was very great. The writer and our surgeon (Pooler) were put on board a brig of war, then commanded by a Lieutenant Blaney (a great tyrant), and remained there for about eight days, when we were put on board the ‘Nelly,’ our Headquarter ship, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell.

The evening that we escaped from the ‘Princesa’ we saw her go to the bottom at about four miles off, so that if Providence had not been pleased to abate the wind nearly three hundred souls would have met a watery grave. Nothing particular happened on the passage, but the death of Lieutenant Thomas Murray, who was suffocated in his berth by leaving his leather stock on. He was a brave soldier and a worthy young man.

We saw no land during the passage, and arrived at the Cove of Cork on the 27th. December, after a passage of nearly seventeen weeks, in the latter part of which we suffered greatly for want of fresh water. The officers were on the allowance of a pint a day, and the men were obliged to suck this quantity through the touch hole of a musquet barrel from the scuttle butt.

When landed we marched to Middleton Barracks, where the men received a year’s pay, reserving sufficient to purchase necessaries, etc.; but such a scene of drunkenness for eight days was never seen in the British or any other army. The barrack gates were closed only when drays from Cork were admitted with barrels of porter and hogsheads of whisky, and in some rooms they were actually ankle-deep in liquor. After some time we marched to the new barracks in Cork, and were completely equipped with arms and accoutrements, clothing, etc., which was sent from London by Colonel Pack, who joined us here. We were also presented with a new pair of colours (the old battalion colours having been captured at Buenos Ayres) by Sir John Floyd, who made the following speech on delivering them:

‘SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT,

‘I am directed to perform this honourable duty of presenting your new colours.

‘Brave Seventy-first, the world is well acquainted with your gallant behaviour at the capture of Buenos Ayres in South America, under one of His Majesty’s bravest Generals.

‘It is well known that you defended your conquest with the utmost courage, good conduct and discipline, to the last extremity, when diminished to a handful, hopeless of succour, and destitute of provisions; you were overwhelmed by multitudes and reduced by the fortune of war to lose your liberty and your well-defended colours, but not your honour.

‘Your honour, Seventy-first, in the field covered you with glory; your generous despair, calling on your General to suffer you to die with arms in your hands, proceeded from the generous spirit of British soldiers. Your behaviour in prosperity, your sufferings in captivity, and your faithful discharge of your duty to your King and Country, you who stand on parade in defiance of allurements held out to base desertion, endear you to the army and the country, and ensure the esteem of all true soldiers and worthy men, and must fill every one of you with honest martial pride.

‘It has been my good fortune to have witnessed in a remote part of the world the early glory and gallant conduct of the 71st Regiment in the field, and it is with great satisfaction I meet you here with replenished and good arms in your hands, and stout hearts in your bosoms.

‘Look, officers and soldiers, to the attainment of new honours and the acquirement of fresh fame.

‘Officers, be friends and guardians to the brave fellows committed to your care.

‘Soldiers, give your confidence to your officers; they have shared with you the chances of war; they have bravely bled along with you; preserve your Regiment’s reputation for valor in the field, and regularity in quarters.

‘I have the honour to present the Royal Colour. This is the King’s Colour.

‘I have the honour to present the Regimental Colour. This is the colour of the 71st Regiment.

‘May victory for ever crown these colours.

N.B. - 96 of our men remained in South America. (17)